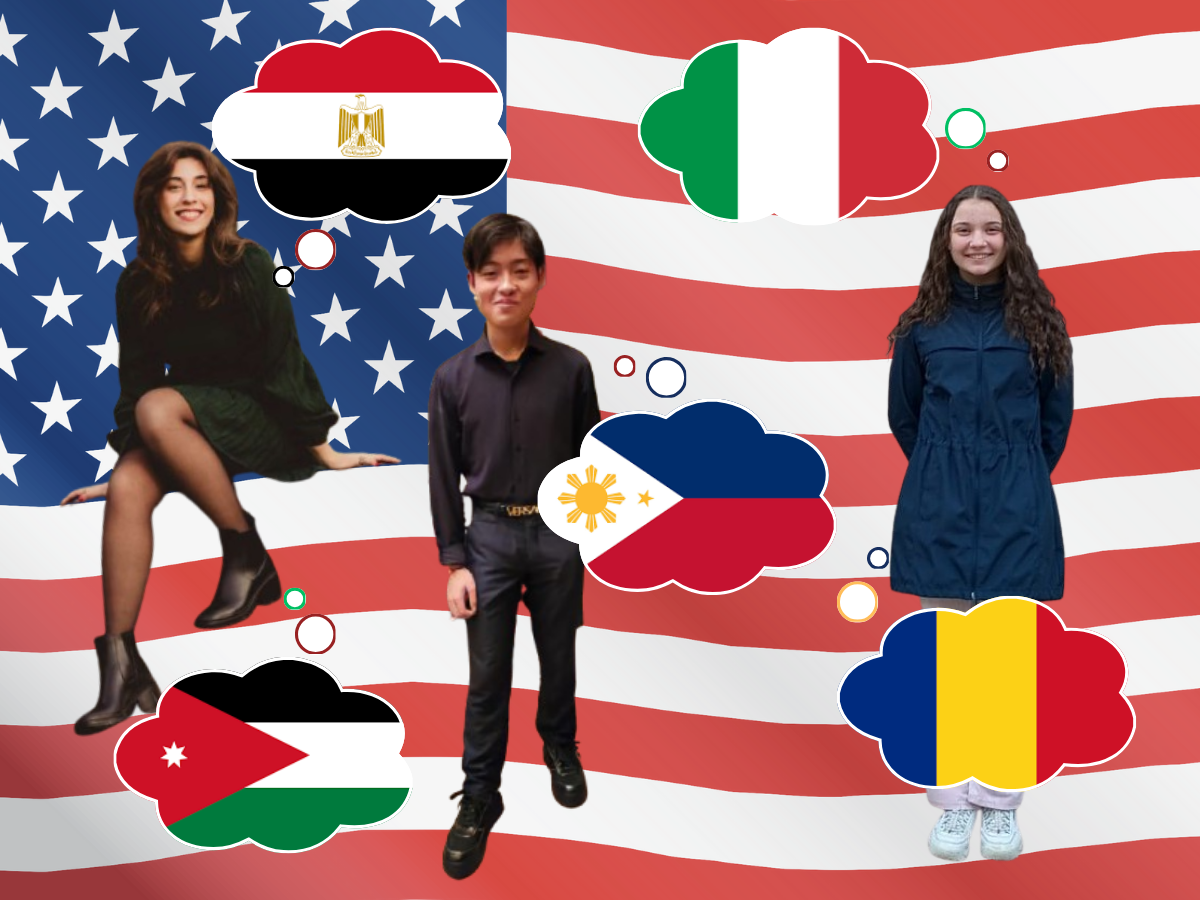

Granville’s proximity to major universities and international companies draws families from around the world– and with them, a growing population of bicultural students at the high school.

Three of these students and a teacher share how they navigate the blending of cultural traditions,expectation and identities in their everyday lives.

BALANCING CULTURES

Junior Xander Connor sees the impact of his Filipino heritage in his family’s daily practices and belief systems he follows

“I always try to not waste any food because there wasn’t much of that laying around where my mom was from,” Connor said. “I respect my elders and adults because that’s traditional beliefs.”

On the other hand, Connor has embraced American culture through his participation in marching band and his familys appreciation for American food.

“We love to eat populuar Amercain food all the time,” Connor said,” Sometimes we would have pizza every other week.”

Senior Sarah Soliman, a first generation Arab-American, also strives towards finding a balance between her two cultures. At home she steps back to her familial roots through the language, food and cultural values, while at school she experiences the mainstream American culture.

“I consider myself very American and very western in terms of culture, and I still very much agree with some values from my Arab culture,” Soliman said.

Soliman finds her Arab cultural background helps her take a more community-minded approach to life, allowing her to introduce a different perspective then her peers.

“Here, individualism is very valued; whereas in Arab cultures, collectivism is very valued.”

Although challenging, Soliman’s ability to balances her contradicting cultural values allowed her identity to weave into her own individualized perspective.

“[Arab culture] influences my morals, ” said Soliman. “And how I prefer to handle situations, whether that means being a little bit more selfless, a little less goal oriented versus community oriented”

Soliman says that her more Western view doesn’t always align with her parents’ perspective.

“Me and my siblings for the most part have a slightly more Westernized view of our morals and our daily lives than our parents do, and this can cause some friction between us when it comes to values and daily interactions,” Soliman said. “We are still trying to learn how to coexist between these two cultures because it’s a hard balance to find.”

FOOD

Cultural food is an important part of these students’ lives.

Sophomore Sarah Crestale, who was born in the Monza-Brianza province of Italy, stays connected to her culture through the food she eats at home.

“I think we eat what can be considered as Italian or Romanian dishes almost everyday, and during holidays we make all our favorite traditional cultural dishes,” Crestale said.

These dishes reinforce ideas of comfort, identity and home for students.

“The Filipino food has been with me since I’ve been alive, and it just feels like home,” Connor said.

Unfortunately, others sometimes view food from other cultures as strange.

“Sometimes people think some of our food is a little weird, especially the Romanian food my mom makes, but it’s actually so good,” Crestale said.

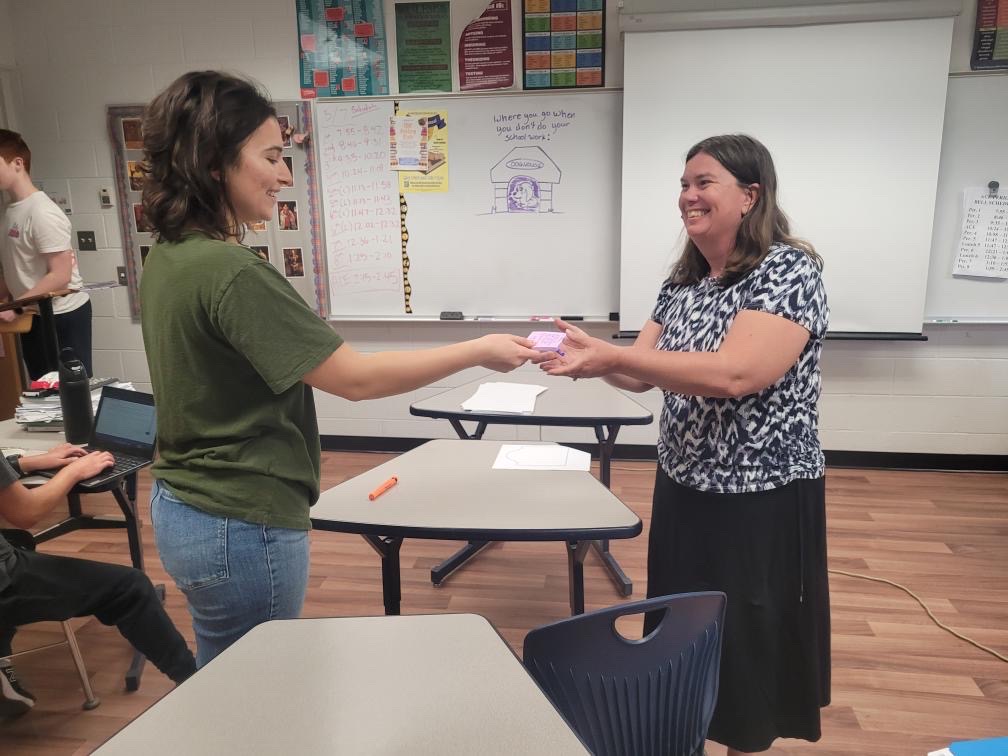

Orchestra teacher Samantha Schnabel has also experienced this while sharing the Korean food from her childhood.

“It sometimes grosses people out, but a huge part of our culture is seaweed soup,” Schnabel said. “Whenever mothers give birth, they’re supposed to spend like a month eating seaweed soup because it’s supposed to nourish the body. Every birthday, they say, you don’t turn a year older until you have your seaweed soup.”

FAMILY

Although multicultural backgrounds have many positive aspects, one negative aspect is being separated from families who remain in countries far away.

Within Crestale’s nuclear family, culture becomes a more intimate celebration simply because there are less people to share it with.

“My friends spend holidays with their grandparents or get to hang out with their aunts, uncles and cousins on weekends and me and my family can’t really do that,” Crestale said, “I think I see my grandparents once every three years in person. We Facetime on the weekends, but it’s not the same as getting to spend time with them.”

SHAPING EMPATHY

Unfortunately, sometimes bicultural students can feel isolated and somewhat embarrassed to express their cultural identities due to negative comments from peers.

Schnabel said she found that in her youth, she faced insensitive prejudice and isolation.

“I was in middle school and the late 90s early 2000s,” Schnabel said. “And I mean, there are just like a lot of stereotypes, and it was a little rough being in middle school, specifically at that time, because I didn’t have a lot of Asian friends.”

Within Schnabel’s experiences she found that people oftentimes lacked empathy and understanding.

“I have very vivid memories of my mom speaking English and she actually spoke pretty well, but, of course, she had an accent, she still does,” Schnabel said. “ I just remember people giving her such a hard time. Like she would say ‘Could I have a vanilla cone?’ but they would always say, ‘Wait, we don’t have banana. We don’t have banana.’ and it was just the most rude thing, because she is not incompetent.”

Schabel adapted and developed into a person who champions the ideals of empathy and understanding. Turning her negative experiences into opportunities of personal growth, she is able to translate these values into all aspects of her life, allowing her to better connect with her students.

“I just felt like it was really important for me to just kind of show my face and you know be here for students who may not have a teacher they identify with,” Schnabel said. “I’ve tried to be a little bit more present in the school community so that students know there are other people out there that they can identify with.”

Barrett Waggoner • May 20, 2025 at 9:40 am

That’s so cool!!!